Written by Adam McIlroy.

14 minute read

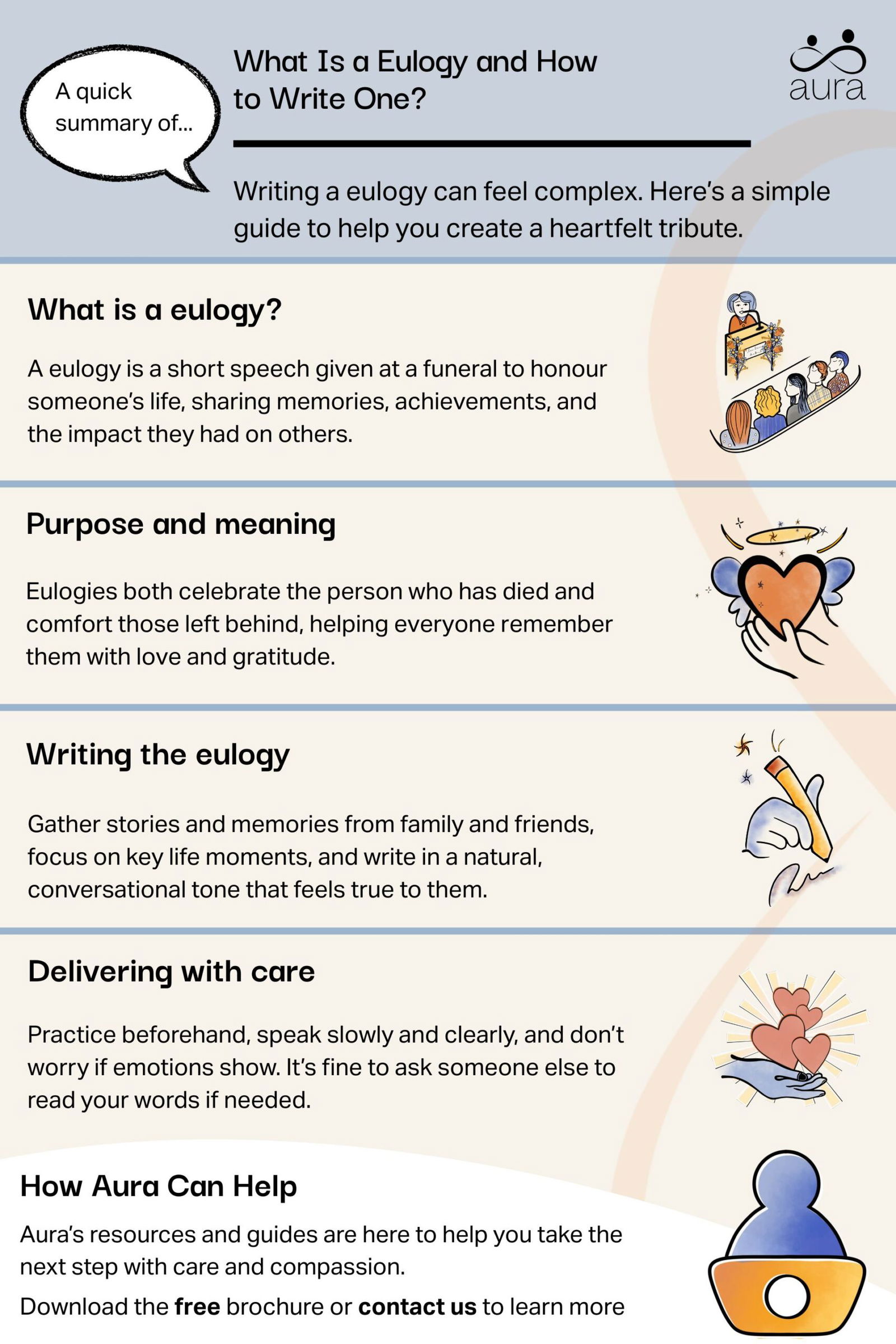

One of the most important elements of any funeral is the eulogy. A thoughtful eulogy can transform a ceremony into an unforgettable memory in the lives of those who’ve attended. In this article, we will answer the question ‘What is a Eulogy (and how to write one)? We will offer some tips on what a eulogy is, how to gather information for and write one, and how to deliver it well on the day.

We’d also just like to recognise that, if you’re reading this, then you may have been recently bereaved, and that you may be facing a complex time. We at Aura are here to help. We are the UK’s top-rated national provider of ‘Cremation Services’ on Trustpilot with a score of 4.9/5 stars. We offer our funeral services to those in need imminently, through our direct cremations, and to those thinking ahead for the future, through our prepaid funeral plans.

Key takeaways:

A eulogy is a speech honouring the life, legacy, achievements, and personality of someone who has died, and is one of the key things that happen at a funeral. It’s one of the elements of a funeral which is most adaptable to personalisation and tailoring to the character and personality of the one who has died. Time for a eulogy is usually noted in the orders of service, if the family have made any.

Its main purpose is to offer a narrative about the person who has died, often focusing on how they’ve lived, their career, their favourite things, and their success as a parent or partner. To hear a eulogy at a funeral is often a great source of comfort to those who’ve gathered to mark the person’s passing.

A eulogy is one of the main elements of any funeral, whether religious or secular, and it has two main purposes: honouring the person who has died, and offering comfort to their loved ones.

A eulogy is normally crafted to build a sense of shared remembrance among the attendees who’ve gathered for the funeral. The one thing which unites those who have decided to attend is the person who has died, so the eulogy can be a powerful moment. It’s important that it should reflect on their character; share some of their witticisms and bon mots; chart their life’s unfolding, through their relationships and achievements; and reiterate how they impacted the lives of those in attendance.

The experience of listening to such a eulogy can be a powerful way of remembering a loved one, helping us to relive some of the most joyful moments we experienced with them in a shared space with others mourning their loss. It can therefore be a great comfort to their loved ones, and can be a powerful first step in saying goodbye, as they pass into memory.

Each eulogy, much like the person whom they seek to remember, is different. That means that different tones and types of content will be more or less appropriate depending on the person themselves. Humour and anecdotes can be used to great effect in telling someone’s life story, and can help it to feel as if they are there again in the room with everyone. But, clearly, the circumstances of their death and the age of the person who has died, among other things, may make this harder to justify, so you will need to use your best judgement.

In preparing to write a eulogy about a loved one who has died, you will need to gather memories and stories from others who knew them; consider the key elements of your eulogy; and think about how to craft a memorable speech. If you’re feeling stuck, it might also be helpful to study some eulogy examples and eulogy templates or inspiration.

To make your tribute as authentic and relatable as possible, try to gather different stories about the person who has died from different corners of their life. Approach their nearest family members, as well as friends and colleagues. These different types of people know different sides of us from the others, so hearing stories from these other aspects of the person’s life can be a meaningful and uplifting experience, showing us the one whom we’ve lost in all their complexity.

You may also wish to review the career and life milestones of the person who has died. These are useful points by which you can chart the course of their life’s narrative, and can help you to organise the structure of your speech. Naturally, it will be useful to write out your speech beforehand according to the general structure of ‘Introduction, Life-story, Conclusion’. The speech can be furnished with a variety of tributes to their memory.

You may want to start by thanking everyone for coming, and by introducing yourself and your own connection to the person who has died. Depending on the beliefs on death and funerals of the person who has died, there may be a large number of people in attendance, and not all of them will know who you are.

You will want to share personal anecdotes and stories about them, particularly which show your own personal connection with them, and which resonate with you authentically. These are the stories which stand the best chance of really capturing their essence, and bringing their spirit back into the room. You may also want to reiterate their beliefs, values, and achievements, and how these guided them through their life and influenced those around them.

Crafting a memorable speech about someone who you’ve lost can be an important part of the grieving process. Feeling that they have been adequately and movingly remembered at their funeral can help us to cope with the death of a parent or other loved one. You may wish to consider using a conversational tone, rather than something more highly wrought and formal, as this stands the better chance of being relatable to most people. Naturally, the decision on which tone to adopt will depend on the kind of person they were and how they lived their lives, so exercise discretion on this point.

Try to keep things as brief as possible. The mourners who have gathered will likely be in a heightened emotional state, so they will only be able to focus on important, simply expressed details. Take your time in the delivery to give them the chance to listen actively and to absorb what you are saying. Remember that it will likely feel to you as the orator that you are moving faster than you actually are, so don’t be afraid that you are pausing for too long, or talking too slowly. A good approach would be to practice the speech beforehand a number of times, whilst timing yourself, to give yourself a good idea of how long you will need to deliver it in full on the day.

In order to write a good and memorable tribute, you will need to balance the emotions of the day with an uplifting, positive message, and you will need to adapt your words to the attendees.

Whether religious or secular, a funeral is unlikely to be an overwhelmingly positive occasion, regardless of how uplifting is the life-story of the person who has died. Those in attendance may be struggling to deal with grief, and to keep their emotions in check. You will have to balance between recognising and reflecting these heavier emotions with charting a more positive course. It may therefore be a wise strategy to avoid lingering on upsetting details, for example of the exact manner in which they died, or on more difficult and sadder aspects of their life-story.

With that said, even if the person who has died lived in a lighthearted and upbeat way, it may be the case that the mourners might not be receptive to a eulogy that aims to reflect this.

As such, it may be a good idea to prepare for this scenario in advance, with some material up your sleeve which you can fall back on should the atmosphere on the day give rise to the need to change course. If you are worried that you will not be able to do this on the day, it may be a better approach to stick to universal themes and messages which can be delivered in whatever way suits best on the day, rather than trying to personalise things too much in one direction or another.

In order to deliver the best possible eulogy, you will need to practice a few times beforehand in order to find your rhythm, and you will need to read with emotion and clarity.

When practising the speech, try to do so at the volume you intend to deliver it on the day. If you are in a room at home when practicing, you will probably feel the temptation to simply speak your words at a normal volume. But, in doing so, you will read them more quickly than you would at the proper volume. This could lead you to end up with an unrealistic understanding of how long it takes to deliver your speech. Reading it aloud rather than simply in your head will also help you to understand the flow, and to identify areas of the text which are bloated or particularly difficult to listen to or to say.

Practicing is important, not just for your confidence on the day, but also for your own editing process. It’s also important for helping you to feel more prepared, and, therefore, less nervous. Speaking in front of a room full of emotionally vulnerable people on such a meaningful occasion as a funeral can be a very nerve-wracking experience. Grounding yourself (consciously noting the feeling of your own feet squarely on the floor) and noting your breathing can help you to gain control of your nerves, and to speak with control and clarity.

By making a conscious effort to read more slowly, you will increase the power and feeling of your words, and make a bigger impact on your audience. It will also give them a better chance to absorb and understand your words. You can also pause for rhetorical effect at moments where it feels right, allowing the emotions to intensify, but also for a moment of clarity, helping the listener to keep up. It’s also natural that you could be feeling more emotional at this point yourself, anyway, as you may be facing a difficult time.

You may also wish to bring a printed copy of your eulogy for yourself, so that you don’t have to memorise your words verbatim. This will give you a greater sense of control and confidence on the day, whilst helping you to avoid that ‘memorised’ tone as you deliver your speech. You could also bring print-outs of your words for the attendees and leave them on the seats, allowing the listener the option to read along with you as you speak, helping them to understand everything more clearly.

We hope that this article has helped you to understand a bit more clearly what is a eulogy (and how to write one). If you’re looking for guidance on this subject, then you might have recently lost someone close to you, or you might be thinking about how to prepare for a funeral in the future.

Aura is a family-run company with a mission to provide compassionate, people-centred funeral services to all those who need them. Our wonderful, industry-leading Aura Angel team are there to assist you or your family throughout the making of funeral arrangements, helping with the paperwork and logistics, and lending a listening ear, if you feel you need to talk. If we can help you with any funeral arrangements you may be considering, why not give us a call?

Depending on the service format, a eulogy should last between 5 and 10 minutes. Funerals don’t last for as long as we might think, so, alongside the other matters, there may not be a great deal of time for extended reflection. Stick to the most important facts, and try not to ramble. Naturally, at an occasion such as an end-of-life celebration after the funeral ceremony itself, it may be possible to speak for longer.

It would be perfectly understandable to become overwhelmed by the occasion, especially if the person who has died was especially dear to you. Aside from practicing the speech a number of times beforehand (in front of an audience, if you can), you could also make arrangements to have a back-up reader step in, should it become a little too much for you.

Others like to simply write the eulogy before having a professional funeral celebrant read it for them, as it’s natural for emotions to run high during this difficult time.

Absolutely – a eulogy can be secular, religious, or a blend of both. There has been a decline in religion in the UK in recent years, leading to a drop in the number of religious funerals in the UK. Nevertheless, non-religious people often still look to include religious imagery and messaging in the content of their funerals, including their eulogies.

But, of course, with a non-religious funeral, there’s no limit to the kind of material that can be drawn upon for helping to write a good eulogy. If you don’t want to use religious texts for inspiration, you can turn to the many examples of stories about death out there, which touch upon universal themes like love, loss, kindness and dealing with grief.

If you’re looking for inspiration from some of the best eulogies ever written, then you can find various good examples online. Barack Obama’s for John Lewis is widely regarded as a classic for its role in cementing Lewis’s legacy as an impactful politician in American history. It can help you to understand how to talk about someone’s achievements.

Another example could be Charles Spencer’s for his sister, Princess Diana. His eulogy balances the uplifting message of Diana’s character and personality alongside the sombre and devastating circumstances surrounding her untimely death. It can help you to understand how to navigate the emotional complexity of writing a eulogy.